Contrary to popular belief, it is given to artists, not politicians, to create a new world order.

Alex Danchev, On Good and Evil and the Grey Zone (2016)

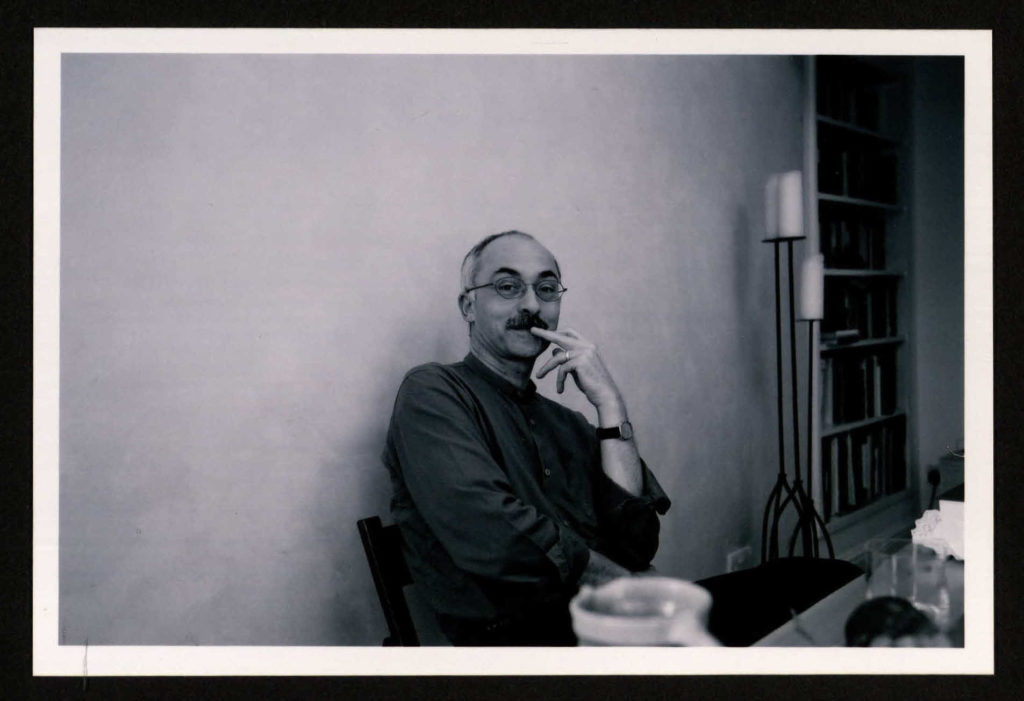

Alex Danchev was Professor of International Relations here at the University of St Andrews from 2014 until 2016, when he passed away unexpectedly. He was well known for his wide-ranging work in modern and military history, politics, and biography, as well as his strong interests in art, literature, and philosophy.

Prior to coming to St Andrews in 2014, his career had taken him from officer in the Royal Army Education Corps, through a PhD in war studies at King’s College London, to posts at Keele University and Nottingham University, with visiting fellowships at Queen Mary University of London, and St Antony’s College, Oxford.

During his time in the School Professor Danchev was a founding member of the Centre for Global Affairs in Philosophy which later paved the way for the birth of the Centre for Art and Politics.

Following his untimely passing Professor Danchev’s wife, Dr Delia Danchev kindly gifted the University library over 2000 books from Professor Danchev’s library. Materials including notes and letters were also donated and the funding for two staff project posts: one archival post and the other a Library traineeship. These posts enabled the University library to record and make the Danchev Collection available for consultation and borrowing.

As part of this generous gift funding was made available in the The Alex Danchev Fund. This fund allows the Centre for Art and Politics to work with others to encourage the sponsorship of artists, curators, and others associated with the Arts, creating the University of St Andrews as an Institution of Refuge for people whose lives are in danger.

Full obituary – Elizabeth Cowling for The Guardian (11th September 2016)

The historian and biographer Alex Danchev, who has died aged 60 from a heart attack, believed that it was artists rather than politicians who had the power to change society.

Danchev made his name as a military historian, with acclaimed biographies of Oliver Franks (1993) and Basil Liddell Hart (1998), and a co-edition of the unexpurgated war diaries of Lord Alanbrooke (2001). More recently, artists had become his focus, although he continued to write about contemporary politics, notably Anglo-American relations and the so-called war on terror. A life of Georges Braque (2005) – the first ever to be published – was succeeded by a life of Braque’s “god”, Paul Cézanne (2012), and Danchev’s meticulous and tone-perfect new translation of Cézanne’s letters (2013) – letters which had formed the backbone of his subtly revisionist interpretation of the artist’s character and behaviour.

An anthology of 100 artists’ manifestos published between 1909 and 2009, including those by Boccioni, Malevich, Barnett Newman and Gilbert and George, came out in 2011. In all these well-received books – and his many essays on contemporary painters, photographers and film-makers – Danchev deployed to brilliant effect his knowledge of the literary culture that helped to form his subjects’ work and thinking. He also wrote beautifully about the visual qualities of the art.

His biography of René Magritte – a painter for whom poetry and philosophy were prime sources of inspiration – was incomplete at the time of his death.

If this mixture of military history, philosophy, poetry and avant-garde art seems eccentric, for Danchev the interrelationships were essential. As he put it in the introduction to On Art and War and Terror (2009), “Armed with art … we are more alert and less deceived.” Artists (in the broadest sense of the term) being exceptionally acute “witnesses” of their times must, he argued, be taken seriously as thinkers and moral agents; their works have political and ethical force. Seamus Heaney’s statement, “The imaginative transformation of human life is the means by which we can most truly grasp and comprehend it” was, he said, his credo.

In the essay on Anselm Kiefer published in On Good and Evil and the Grey Zone (2016), Danchev expressed this controlling insight in characteristically pungent style: “Contrary to popular belief, it is given to artists, not politicians, to create a new world order.”

Alex Danchev was born in Bolton, Lancashire. His father, Alfons Danchev, was a mining engineer of Belgian and Bulgarian parentage who moved to London to complete his training in 1939 and, having worked for the BBC World Service during the second world war, became a British citizen in 1947. His mother, Anne Gilman, worked in the fashion industry. This background no doubt contributed to Alex’s dislike of conventional boundaries and eventually to the impassioned opposition to binary thinking (“us and them; black and white; good and evil; civilisation and barbarism”) expressed in the essays gathered in On Art and War and Terror, and On Good and Evil and the Grey Zone.

A first-class degree in history and economics at University College, Oxford (1977), and a postgraduate teacher-training certificate at Trinity Hall, Cambridge, were Danchev’s passport to Sandhurst in 1978 and the start of a decade as an officer in the Royal Army Education Corps. Meanwhile, he completed a PhD in war studies at King’s College London (1984). A research fellowship at King’s in 1988-89 spelled the end of his army career and led to a lectureship in international relations at Keele University, with promotion to professor and head of the department in 1992.

From Keele, he moved in 2004 to the school of politics and international relations at Nottingham University, and from there, finally, to St Andrews University in 2014. Successive high-profile visiting fellowships at Queen Mary University of London and St Antony’s College, Oxford (2008-10), reflected the esteem in which his work was held.

Danchev’s energy was phenomenal: his commitment to teaching, for which he won several awards, remained intense despite his stream of publications, arduous administrative duties and membership of august editorial boards. Somehow, he also found time to review regularly for the Times Higher Education and Literary Supplements, the London Review of Books and the Guardian. Reviewing sometimes triggered a major new project. Thus an exuberant response in the THE to the Magritte exhibition at Tate Liverpool in 2011 – “My advice: jump on a train to Liverpool and marvel afresh at all the things there are to marvel at” – was the catalyst for his unfinished biography of the artist.

Among the qualities that made him so original and stimulating a historian of 20th-century and contemporary politics and art was his imaginative and creative response to an exceptionally wide range of cultural material. Typically, he prefaced his essays with quotations from thinkers and writers that proved to be perfectly apt, but that belonged to a period or milieu seemingly different from that of the subject in hand. Thus a sharply worded assessment of Tony Blair’s role in the Iraq war was introduced by Aristotle’s Ethics.

Montaigne, Proust, Nietzsche, Kafka, Rilke and Beckett were among favourite points of reference, but the chorus of voices was neither stable nor predictable: it was always expanding to admit discoveries or rediscoveries. So, following a characteristic pattern, Danchev’s research on Magritte led to his delighted discovery of the underrated Belgian Surrealist poet Paul Nougé, who duly joined the select company worthy of quotation in an epigraph.

Thinking laterally was one of Danchev’s fortes and the mot juste another, for the dazzling erudition never came with the heavy hand of the pedant, but with the striking turn of phrase of the enthusiast keen to share with his readers the joys and revelations afforded by the books that had marked him.

In his life and in his work Danchev was sustained by his partnership with the psychologist Dee Cooper, whom he married in 1998 and who, he said, immeasurably deepened his understanding of the complexities of human nature.

A devotee of jazz, he relished good company and the good things of life, while not seeking to conceal his streak of moral earnestness. He is survived by Dee, his step-daughters, Sarah and Jemma, and his step-grandchildren, Alexander and Isabella.

Alexander Danchev, historian, born 26 August 1955; died 7 August 2016